YES BUT NOT QUITE

Three days after my swab test, I was waiting for a phone call I dreaded to receive. That was what they told me: to wait for 3 to 5 days. It did not come on the third. Neither did it come on the fourth. On the evening of the fifth day, I received a call from DOH: “You are positive for COVID-19. Have you been on self-quarantine?”

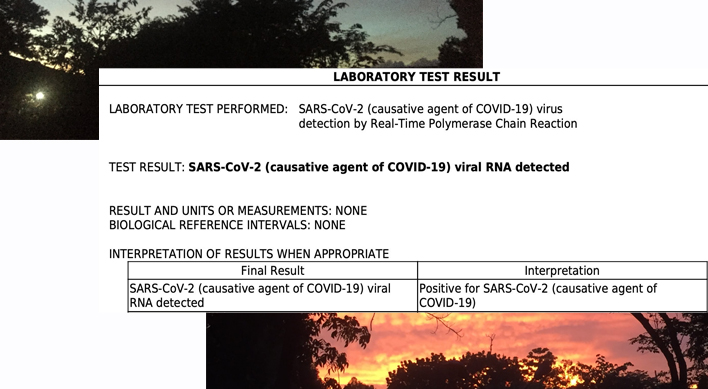

Later, I received an email from the RITM through the hospital: SARS-CoV-2 (causative agent of COVID-19) viral RNA detected; Positive for SARS-CoV-2.

I did not know what to feel. First things first. I had to email my superiors, confreres and people who live with me in the same house. I had to inform my staff to take precautions, especially those who were working with me in the last few days in school. I had to tell my family and some friends for them not to worry. I was having a little fever, dry cough and had no appetite. I suffer from LBM, sometimes feeling cold and ironically perspire a lot at night. But that’s about it. It was actually not serious.

I feel it was manageable; I did not write many of my friends. I did not want people to worry about me. In fact, this is the first time I write my reflections about it. I was re-tested and am negative now. But it still took me some days to write about this experience.

Like all intimate experiences, it is too personal that one is at a loss for words. Yet because it is most personal, it is also the most social. The complex feelings inside me are fully intertwined with the complex COVID-19 world around. And this risky world reproduces its complexity within the world inside me.

A priest-friend who knew about my being positive wrote me: “I pray hard for you. Keep heart. You were with them. Now you are one of them.” I did not reply to him. But I told myself: “Yes but not quite.”

FEAR AND DUTY

Someone asked me: “Was there a time during this ordeal that you were afraid to die?” Of course, there was. I had co-morbidities myself. I am not that young anymore to have that needed resistance. I have relatively high diabetes. When I arrived in the hospital, I was diagnosed with upper respiratory tract infection. I did not quite understand the jargon but I can sense it has to do with the lungs which is most vulnerable for COVID’s attack. However, I still thought I can manage it. I did not find breathing hard. I am up and about. In fact, I can still drive back home after the swab test. But when I think that some of my friends who were younger went under the respirator, the fear of death became real.

In the midst of fear, a lot of things come to one’s mind. What if? Maybe I could have been more careful; maybe I could have heeded some friends not to join the relief operations all the way; maybe I just have stayed inside the house and avoided any outsider, etc.

But what puts me to my senses is a young nurse who did the swab test on me. She was going around all the patients in the emergency room. There was more than a dozen of us at that hour. She was in PPE but you can only imagine how many potentially positive patients she gets in close contact with each day. When it was my turn, I asked her if this is her job every day. She said yes. “Are you not afraid to be contaminated?” “I am. But it is my duty to do this. So here I am,” she softly answered me and proceeded to the next patient. I kept quiet the whole time at the ER. She kept me asking: “Me, what is my duty?”

The government protocols enhance this fear. Violent military presence reinforces it. We are in the state of war. Obey or you die. Any quarantine violation means imprisonment. This politics of fear leads to many thoughtless impositions – back ride prohibition without marriage contracts, motorcycle barriers which was a road hazard, wearing masks while alone in one’s car, and other “crazy” things – only to be withdrawn later. Regardless if one is hungry or sick, the police violently neutralize you, sue you, imprison you.

And we sadly reproduce and mimic the politics of fear in our little homes, in our places of work, in our churches, to the point of being OA (overacting) – sometimes already hurting feelings of people or forgetting their actual needs. Our deep insecurities possess the inherent tendency to impose. I understand our frantic sense for self-preservation. But I do not understand the insensitivity and inhumanity that it fosters.

One father who was a scavenger risked being caught or imprisoned at the middle the lockdown. He told me: “Ma-COVID na kung ma-COVID. Makulong na kung makulong. Pero hindi ko kayang tingnan na tumurik ang mga mata ng anak ko sa gutom.” (I don’t mind contracting COVID. I don’t mind being imprisoned. What I could not take is to see my children die of hunger.)

Fear for the virus is real. Yes, but not quite. Like the nurse, this father knows that duty needs to confront fear.

ISOLATION AND LONELINESS

Like all patients, I had to be quarantined for fourteen days – and maybe more since it took time for the swab results to come. The isolation can be boring. People were afraid of me. I could not do the things that I needed to do, more especially so at the beginning of the school year. I was also feeling weak and was not in my best self. There was a time that I didn’t want to eat. All food had no taste. I felt like vomiting when I see them. I was looking for the food from my childhood. My kind brother who was working an hour away had to cook some for me and bring it.

However, I had some plants to take care of. I had time to talk to them asking them to heal and grow. I had internet if I want to work a bit or listen to music. I have also cleaned my room of its cobwebs and dust after a long, long time. I can get out of my small balcony and see the moon or the stars at night. I have not sat in this balcony for years of stay in this room. It gave me chance to whisper a little prayer for people I care about or for those who are sick like me under the moonlight.

But was I lonely? Yes but not quite. I know that my situation is a privileged one. Someone cooks for me and brings food to my room. My family and friends called or sent messages of encouragement. While in my isolation, I was imagining how many suffer real loneliness today. How many are isolated and had to hurdle it alone in their lonely apartments without anyone? fHow many of them do not even have windows or balconies to look beyond? How many families do not have the luxury of single isolation rooms when someone is inflicted with the virus? How many patients struggle with the disease by themselves and die alone without the benefit of a hug from family members, the assurance of religion’s last rites or a proper time for grieving?

How many are hiding in fear inside their homes not wanting to see anyone?They keep trembling without knowing what is going to happen the next day to themselves, to their children or to their loved ones who are far away. This sense of insecurity inflicts panic and paralysis which no assuring word or professional therapy can heal. The authorities were recently alarmed of the rising mental health cases in the country - almost without knowing that they are the ones reinforcing it.

While we still find it hard to process these complex feelings inside us, we see a government that does not give assurance at all. All we hear are endless recorded ramblings, cush-words and dirty fingers at midnight; deep corruption in PhilHealth and the health department; senseless bills being filed in Congress like changing the name of the airport or making Marcos’ birthday a holiday; closing of a local media company and authorizing a foreign one, reclaiming Manila. Bay with white sand, etc. These are all happening while the COVID cases are rising and hospitals are closing.

While people are looking for some assurance that things will be better, or at least clear directions toward some solutions beyond waiting for that miraculous vaccine, there seems to be no one at the helm and this country is going to the dogs.

I thought my isolation was manageable and negligible. Yes, but not quite. In this administration, my little isolation and the hunger of millions transforms itself into real nightmare, pain and loneliness.

RISK AND DARING

I was talking with my staff recently. She was so afraid of the virus that she agreed to “hide” in the seminary for the safety of her children. She hardly permitted them to go out of their rooms. For her, all that comes from outside are dangerous. Then, I tested positive. She later told me: “I thought the risk was outside. Now, the risk has come inside. No one is really sure now. Risk is everywhere.”

I once thought that if you have recovered from the virus, you are already safe. In fact, you can donate your blood plasma for others to recover. No, the immunity is not forever. One doctor tested negative, went home to her family, only to be admitted again and later died of COVID-19. The virus has mutated to something or medical science has not really understood it fully, that we are continuously at risk.

We are in a risk society. The great sociologist, Ulrich Beck, wrote a book of the same title years ago. He says we are “living on the volcano of civilization”. It makes it quite dramatic that COVID-19 came to the Philippines after the eruption of Taal which was the symbol of our seemingly successful business and touristic adventures. It all came to a halt. The volcano of consumerist modernity has erupted and we are ushered into an industrial risk society, the main symbol of which is COVID-19.

Are we doomed? Yes, but not quite.

In my life, I have always been looking for some signs of hope. In the midst of hunger and pain, this is the only way to go on with life. When risk is all around us where do we find hope?

I turn my eyes to a courageous group of women-leaders in Payatas who have risked their lives and safety to distribute rice, pandesal, milk, vegetables, fish and what have you to their neighbors for six months now since the lockdown. After some months into the relief operation, we gathered and sat down to reflect about our work as we do every Sunday afternoon. I asked this guide question: “After three months and with all the risks of being contaminated, why are you still here? What made you stay?” One mother summarized her group’s sentiments: “What made us stay? It is Jesus’ command to feed the hungry. For how can we continue to live when people are dying?”

Such a daring response puts many of us church people to shame – we who are paralyzed by fear, self-preservation or utter complacency.

Yes, but not quite. For I have also seen courageous and brave lay leaders, religious and clergy who dared like the nurse, the scavenger, and the BEC mothers and creatively find ways to bring glimmers of hope in these difficult times.

I would like to thank those who prayed and cared for me during those trying times. You are a sign of hope for me. God help us. S/he is our only hope.

Daniel Franklin E. Pilario, C.M.

St. Vincent School of Theology

Adamson University

danielfranklinpilario@yahoo.com

08.04.2020